to joy (1950)

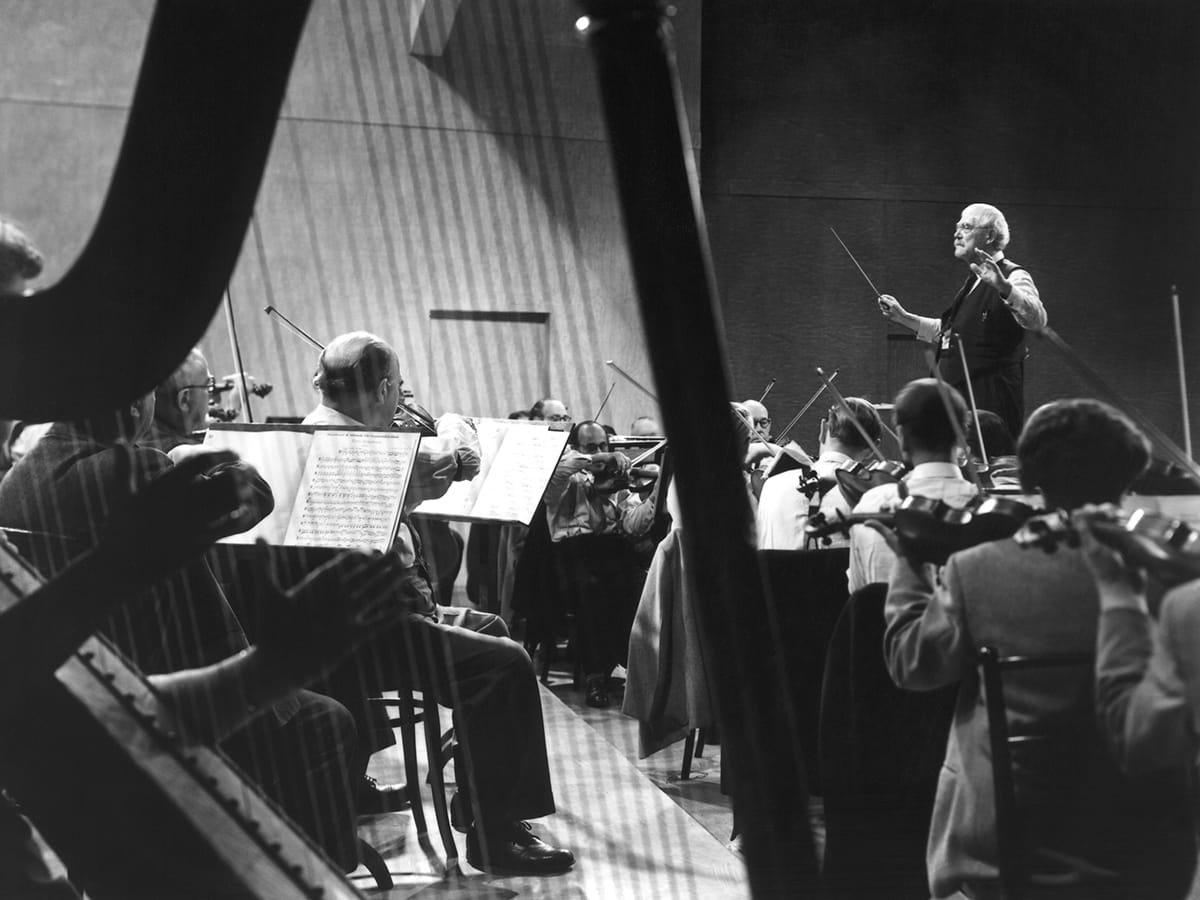

The triumphant serenade of the work of old masters, played by those who wish to be great artists and have settled for a life more ordinary. Bergman’s To Joy settles for a film more ordinary as the script keeps itself aloft for the duration, but never had the needed momentum to reach cruising altitude let alone find its destination. As an ode to life love and ambition, the key emotion here being ambition, which tears apart the would-be successes of our main character, confounds his every advancement with a wave of self-sabotaging blundering and eats his relationships alive. What Bergman lacks in narrative steam he almost makes up for in his script’s free form, his willingness to break that form at any moment to find a road less travelled by the film so far and with elegant new waves of cinema. The pieces which linger on the orchestra so we may relish the pieces are a grand set of scenes which could have easily been cut in an effort toward plot expedience, but are essential to the flavor of the whole, a wise choice. About an hour into the picture we are suddenly narrated in the perspective of the Sjostrom’s conductor character, and never before nor after do we take this vantage point as an audience, yet the foray is one of the film’s high water marks. It is fanciful in Bergman’s usual way, a piteous and self-deprecating narrator, putting down his ability to narrate while continuing to speak to us, the poetry on display in To Joy is just that, those who doubt their abilities but go on trying to succeed at their chosen endeavors in life.

Their self-doubt gets the better of them more often than not, but the film’s final dark conclusion reminds us that our chances for redemption are numbered. We can, at times, have a second crack at getting things right, but when life opens its arms to the individual and the individual shuns life, that same individual will beg and plead the second life turns its back once again. Such is the case with Marta and Stig’s relationship, such is the case with their careers. The film soars as the orchestra takes over, just like the spirits of Marta and Stig but it cannot last forever. Stig’s devotion is to being a great artist, he despises his contemporaries and friends as useless eaters, he despises his conductor for succumbing to his own mediocrity, he despises himself for not rising above them all in some way. He desires to transcend life with his art and to elevate his soul above its station, but at every move he sinks back into the mud, when he achieves the adoration of the crowd he attempts to refuse his bow. Great artists, in Stig’s mind, don’t take their bows. Sjostrom’s conductor character, with the wisdom of his own life’s ups and downs, forces him back onto the stage. But in an ode to life’s joys and its woes, Bergman has brought us a tale that is less able to live and breathe and feels lifeless and uninspired. When Stig brings Marta a bear for her birthday, when the couple are finally wed, when they part, when they reunite, etc.; all should have the trappings of an effective love story and tragedy and yet not for one moment does it ring out louder than a whisper.

When Stig begins to cheat on Marta, it solidifies their falling out and yet the nature of it remains largely mysterious. One of the orchestra players remarks early in the film that he would like to gift Stig to his young wife as a surrogate for making love in his old age. Stig at first refuses his advance, but as the years go by, Stig takes the offer. The film becomes an exploration of ambition and settling, the pull between the two that creates such inner conflict for Stig, he desires things so far outside of himself, and yet in life he looks to what is right next to him and engages with it, rather than go to get what he wants. As the curtain falls on the film, Stig’s surviving son sadly enters the concert hall and sits in wait as his father continues to play, to lose himself selfishly in the music to drown his sorrows. Still does Stig see the tragedy as personal fuel for his dreams of great artistry, rather than turning to the son and becoming a father to him. The ones we should be caring for are left by the wayside as go through the life that the artist needs to live, and yet many of those who live by those principles never reap the rewards of such, only the consequence. To Joy is fertile ground on which to tell the tale, yet Bergman’s execution of it leaves much to be desired as the film never really connects.

6